Where is the abyssal zone located?

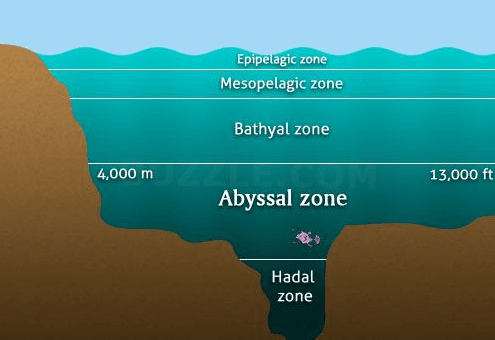

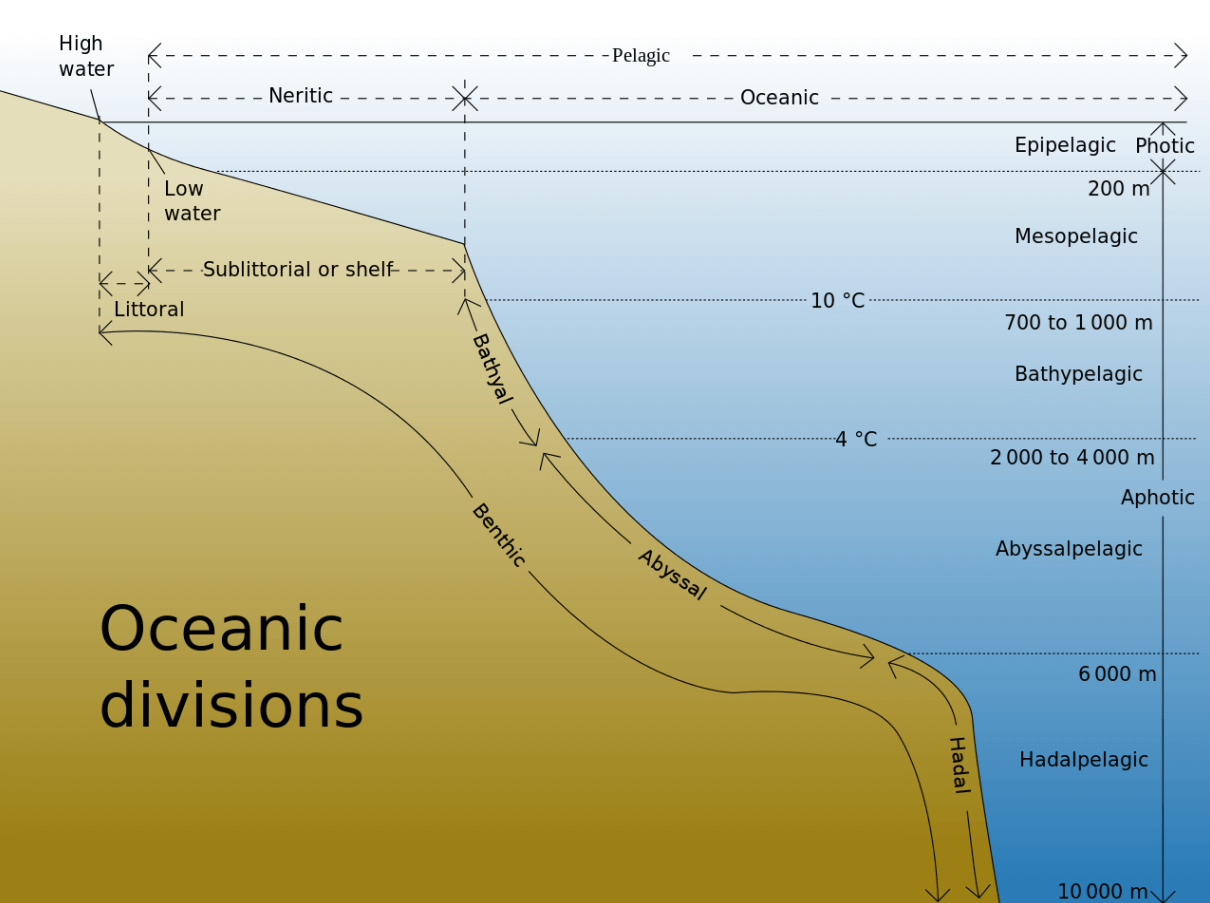

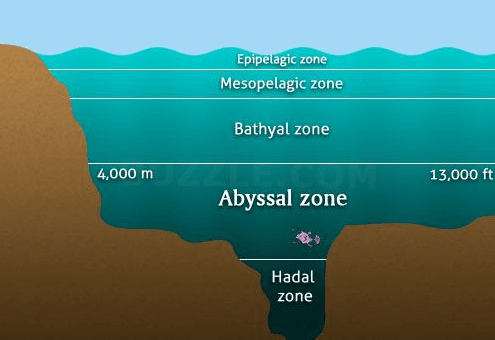

The extensive physiographic province described as the deep ocean floor is classified as an abyssal zone: in these high pressure and low temperature regions, depths are generally between 3,505 and 5,486. 4 m, and temperatures range from 0°and 3.9 C

The abyssal zone comprises substrates (bottom sediment layers) and supports many species of bottom life. Although the number of organisms per unit area is low compared to continental shelves, biological diversity is high. No cost-effective technologies were invented to support commercial fishing or to extract minerals in this area.

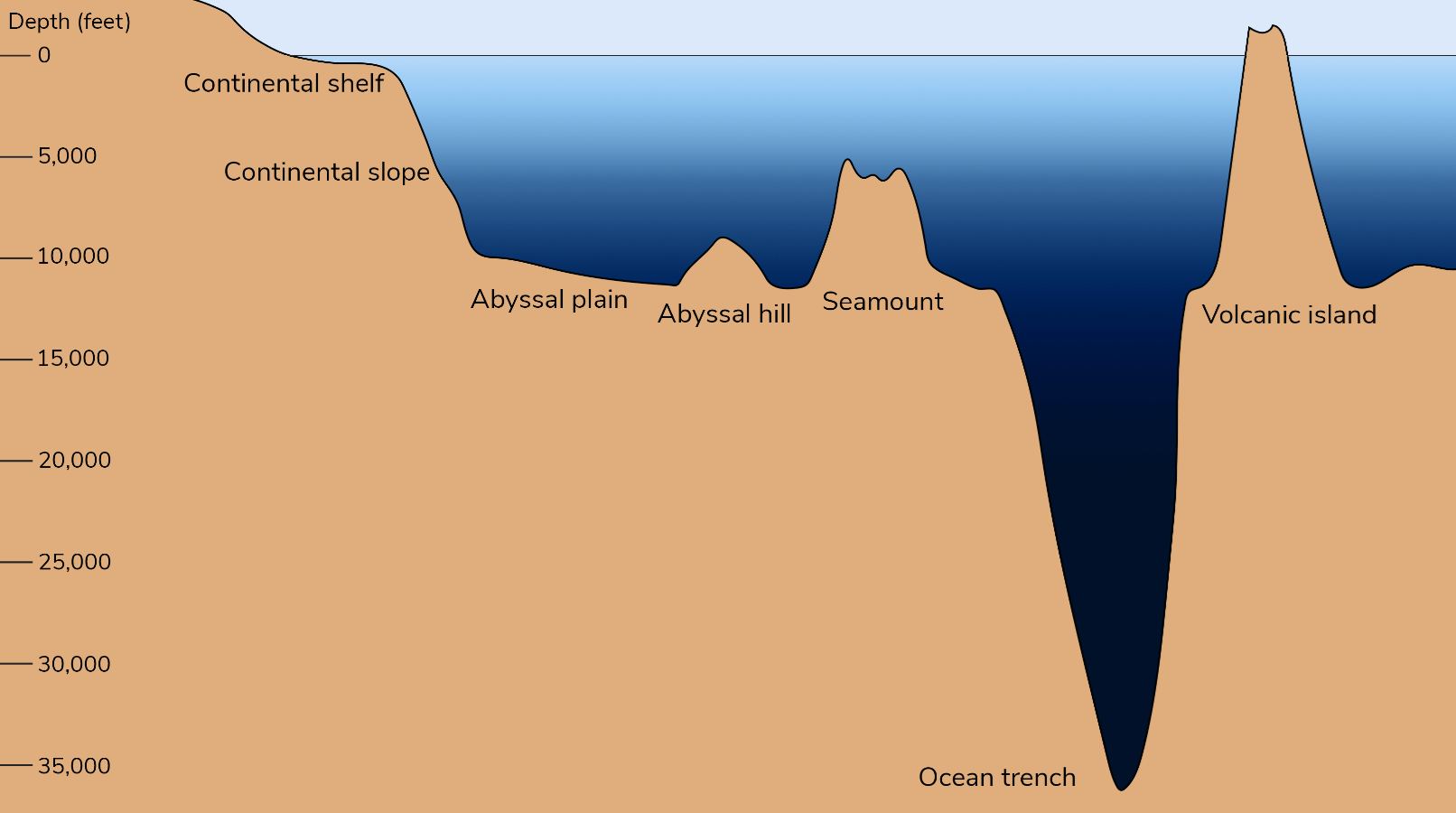

Features common to abyssal zones include mid-ocean ridges that contain hydrothermal vents, classified according to their temperatures. Chemosynthetic bacteria (which metabolize chemicals) thrive near hydrothermal vents thanks to the large amounts of hydrogen sulfide and other minerals from which they draw energy and form the basis of the food web, so much so that they are from giant tubular worms, specialized species of crabs and shrimps.

So, contrary to what one might think, the deep ocean is an active system, in which conditions are maintained by complex interactions between biological, chemical, geological and physical processes. The rhythms of these processes can be relatively slow, but they determine a state of dynamic equilibrium. The ecosystems they support can be damaged by humans, but they seem to resist natural and anthropogenic changes.

Abyssopelagic zone

From the abyssal zone can be distinguished the abyssopelagic zone, composed of seabed that lie beyond the continental rise and that generally extend from 3,505 m deep to the seabed. The only deeper zone is the Adelagic zone, which includes trenches and depth canon The depth of the deep pits can be between 4,998.7 and 2,865 meters while the temperatures in the abyssopelagic zone range from 0 C to 3.9 C

Abyssal waters are very different from the shallow seas found on continental shelves. Sunlight is in fact completely absent and currents and turbulence are relatively weaker than those measured in surface and intermediate waters. Despite this incredibly harsh environment, there is life: abyssopelagic organisms live and feed in open waters between 3,505 and 6,000 m deep, where the pressure is as much as 600 atmospheres.

These deep waters are home to many species of invertebrates, such as basket stars and deep-sea squid. Most species are scavengers called detritivores, who live under the constant rain of dead creatures from the sunlit upper part of the ocean (the detritus). Organic aggregates in the water column are also called sea snow. There are, however, predators: the deep jellyfish, a relative of the jellyfish, captures with its tentacles small crustaceans, larvae and organic debris and digests them in its central cavity.

To survive in the depths, fish have developed special features such as large mouths, elastic jaws and bioluminescent baits to attract prey. The abyssal grenadier (Corph Phaenoides armatus) or smooth-scale mouse tail is found at these depths, all over the world.

Furthermore, consider that bioluminescence is extremely important for many deep-sea creatures. It is present in a wide range of organisms, from bacteria to vertebrates, both on land and at sea. Within the deep waters and seabed, creatures that shine and blink create their own light to survive.

Two important chemicals from the abyssopelagic zone are required for bioluminescence. Luciferin produces light when the enzyme luciferase is present to drive or catalyze the reaction. Bioluminescence in the abyssopelagic zone is believed to aid navigation, to attract prey, to confuse predators, to communicate and to attract mating partners. Currently, there are no cost-effective technologies for using abyssopelagic resources.

Where is the abyss located in the world?

Where is the abyssal plain located?